Speech neuroprosthesis devices have so far focused on translating signals in the brain into words in one language.

But researchers at UC San Francisco, led by neurosurgeon Edward Chang, MD, have now developed a bilingual speech decoder that allowed a man with severe paralysis to easily switch between spelling out sentences in English and Spanish. Their findings, published on May 20 in Nature Biomedical Engineering, represent a significant development in enabling people with speech loss to express themselves more fully.

“Over half the world is bilingual and use each of their languages in different contexts,” said Alex Silva, a UCSF MD-PhD candidate and the study’s first author. “Our goal was to expand the technology to those populations and facilitate very naturally being able to use both languages and switch between them.”

The study continues the Chang’s lab work with a man named Pancho who lost the ability to speak following a brainstem stroke. As part of a clinical trial, he had an electrocorticography (ECoG) array implanted on the surface of his brain — over the sensorimortex cortex and inferior frontal gyrus. Neural activity in these regions encodes the movements of a person’s vocal tract that generate speech sounds. In 2021, Chang and his colleagues first demonstrated that, with machine learning algorithms, they could parse the brain signals during Pancho’s attempts to vocalize into text on a screen.

English is Pancho’s second language though, so in this new study, the researchers wanted to expand to the vocabulary with their sentence-decoding approach to include his first language Spanish.

Some prior studies had suggested that learning a language later in life might mean that the brain represents each of them through more distinct patterns of neural activity. But interestingly, the Chang lab found that the brain’s representations of speech are similar across both languages.

“What we found instead is that, at the level of these neural populations, the cortical activity is actually very shared between the two languages,” Silva said. “There aren't any electrodes that we found that were very specific to one language.”

This allowed decoders to generalize across a set of syllables common to both languages. “The models trained to decode, or classify, these syllables could generalize across the two languages really easily,” Silva said.

In fact, Silva says, the brain activity was so similar across the two languages, it was initially challenging to decode between English and Spanish. He and his colleagues turned to machine learning approaches called natural-language models, which predict how likely different words are to occur together in a sentence in both languages.

These models helped them distinguish whether a string of speech attempts was in English or Spanish. This allowed the system to decode Pancho’s intended language without him having to manually specify which language he was trying to speak.

“Our work supports the hypothesis that as you’re learning a second language, you fit the vocal tract movements and sounds into the framework of your first language,” Silva said.

Since the brain activity was so similar across both languages, the researchers were also able to use data acquired in English to train the decoding models in Spanish more quickly. The models also remained accurate without needing any further training data for more than two months. Silva says these findings mean participants wouldn’t need to spend a lot more time collecting new data in their second language, which makes the technology easier to use.

With newer generative artificial intelligence algorithms and higher density electrode arrays, the researchers believe their approach will scale to larger vocabularies with higher accuracy.

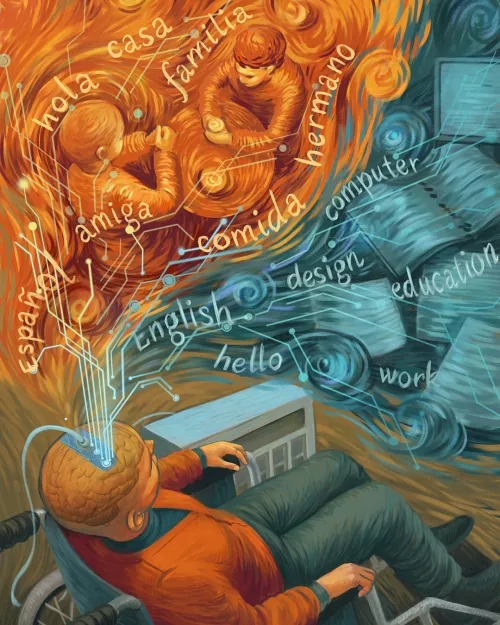

And for the participant Pancho, the new technology gives him back the ability to communicate naturally in both languages he speaks. In the future, he can switch between using Spanish when he’s at home with his family and English when he’s in more formal and professional settings.

Reference: Silva AB, Liu JR, Metzger SL, Bhaya-Grossman I, Dougherty ME, Seaton MP, Littlejohn KT, Tu-Chan A, Ganguly K, Moses DA, Chang EF. A bilingual speech neuroprosthesis driven by cortical articulatory representations shared between languages. Nat Biomed Eng. 2024 May 20. doi: 10.1038/s41551-024-01207-5. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38769157.