A recent analysis led by researchers at UC San Francisco, the University of Washington, and other U.S. institutions offers the first comprehensive report on the contemporary neurosurgical practice for patients hospitalized with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Using the TBI Common Data Elements standards outlined by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the results summarize the clinical profile of surgical patients in the Transforming Research and Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury (TRACK-TBI) Study. TRACK-TBI prospectively enrolled patients with TBI at 18 U.S. level I trauma centers, including Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, from 2014 to 2018. With over 2600 patients enrolled in the study, TRACK-TBI represents the largest modern cohort of Americans with TBI.

The new findings, featured on the cover of this month’s issue of The Lancet Regional Health: The Americas, lay the foundation for future studies investigating how additional clinical factors like diagnostic blood-based and neuroimaging biomarkers and polytrauma could improve surgical decision-making algorithms.

“Our understanding of the surgical population in TBI has greatly advanced in the last 20 years,” said study co-first author and chief neurosurgery resident John K. Yue, MD.

More complex injuries

Most TBIs are mild and, therefore, don’t require surgery. In the TRACK-TBI cohort, the researchers found that only 13 percent of the 2032 patients hospitalized for TBI had surgery. Unsurprisingly, patients requiring acute cranial surgery were more likely to have severe TBI.

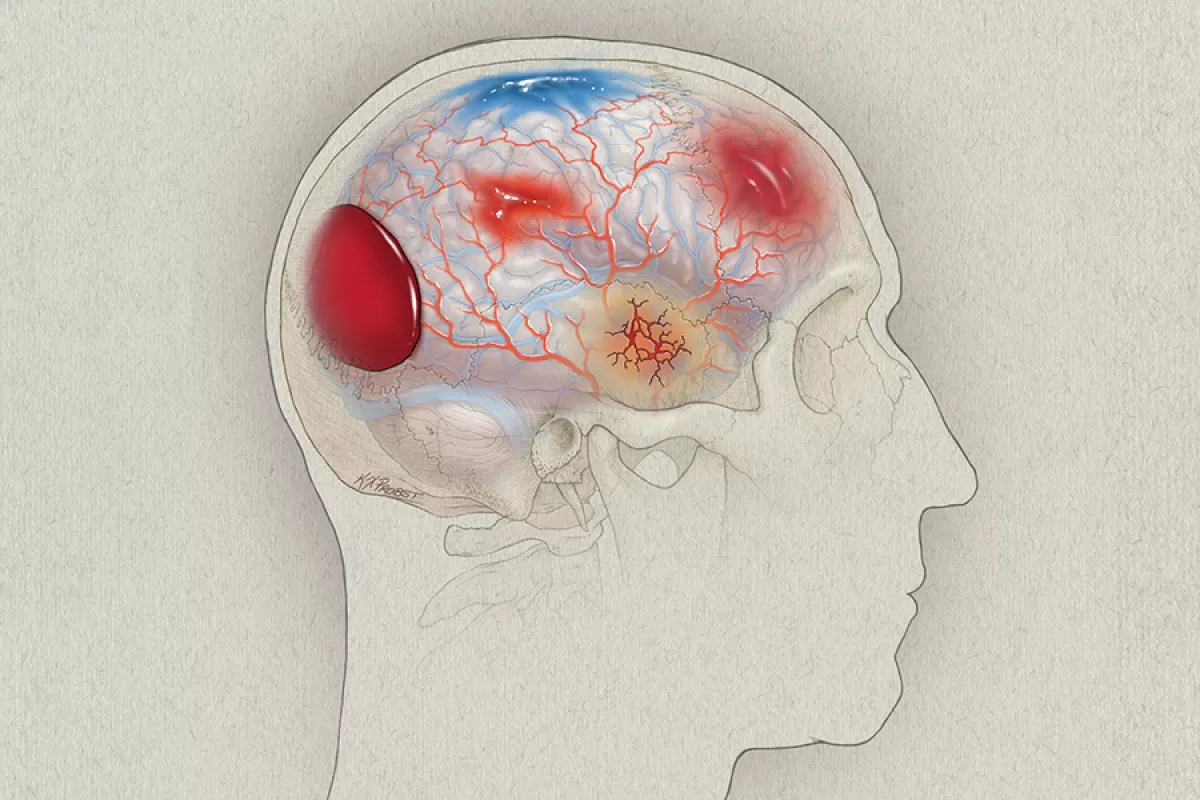

For cranial neurotrauma, neurosurgeons most often perform decompressive craniectomies, in which the skull bone flap is not replaced after surgery, and craniotomies, where the skull flap is replaced. They use these procedures to drain hematomas in the epidural or subdural space or to decrease pressure on the brain.

The Brain Trauma Foundation’s surgical guidelines for severe TBI, which were last updated in 2006, advise on the appropriate treatment based on the type of injury. However, 73 percent of patients who underwent a decompressive craniectomy and 58 percent of patients who underwent a craniotomy had three or more types of lesions.

Even epidural hematomas were not isolated lesions in the TRACK-TBI cohort, contradicting historical TBI data but corroborating a more recent study in a multicenter, prospective European cohort.

“Multifocal TBI cases are more complex than just a singular type of lesion,” Yue said. “That should prompt an update to the surgical best practices for neurotrauma with a more integrative assessment of how to care for these patients.”

In accordance with the current guidelines recommending surgery within six hours from time of injury, 71 percent of patients in the TRACK-TBI surgical cohort received surgery within four hours.

“Contemporary TBI patients are getting the emergent or urgent surgery they need, when they need it,” Yue said, “which means that at U.S. level I trauma centers, we have robust neurotrauma support, including the personnel and hospital-wide systems in place.”

Patients who didn’t go into surgery right away had slightly higher rates of extracranial trauma. Treating this subgroup of surgical patients is more complicated – with previous work showing that patients with TBI who had extracranial surgery and received anesthesia have worse outcomes than those who didn’t. Yue says researchers are beginning to better understand this population of patients and the factors influencing the timing of their surgery, including critical comorbidities and polytrauma.

“In TBI, consideration of lesion type, location, volume, severity and eloquence of the region – in addition to brain compression and herniation – are becoming increasingly important for the management of primary brain injury and secondary brain injury that may evolve or progress over time,” he said.

He adds that this descriptive study lays the groundwork for moving away from the historical classification of TBI as mild, moderate, and severe. These efforts would provide a more nuanced approach to diagnosing and managing TBI that integrates a patient’s clinical profile with blood-based and neuroimaging biomarkers of their injury.

This work is already underway, with the American College of Surgeons publishing a report with their updated best practices recommendations for managing TBI at the end of last month. The expert panel was chaired by this surgical study’s co-senior author Geoffrey T. Manley, MD, PhD, who is also Professor and Vice Chair of Neurosurgery at UCSF, and Chief of Neurotrauma at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center.

Reference

Yue JK, Kanter JH, Barber JK, Huang MC, van Essen TA, Elguindy MM, Foreman B, Korley FK, Belton PJ, Pisică D, Lee YM, Kitagawa RS, Vassar MJ, Sun X, Satris GG, Wong JC, Ferguson AR, Huie JR, Wang KKW, Deng H, Wang VY, Bodien YG, Taylor SR, Madhok DY, McCrea MA, Ngwenya LB, DiGiorgio AM, Tarapore PE, Stein MB, Puccio AM, Giacino JT, Diaz-Arrastia R, Lingsma HF, Mukherjee P, Yuh EL, Robertson CS, Menon DK, Maas AIR, Markowitz AJ, Jain S, Okonkwo DO, Temkin NR, Manley GT; TRACK-TBI Investigators. Clinical profile of patients with acute traumatic brain injury undergoing cranial surgery in the United States: report from the 18-centre TRACK-TBI cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2024 Oct 17;39:100915. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2024.100915.