Medicine may be rooted in science, but it has never been wholly driven by it. The human body and mind are so complex that progress in medicine depends more and more on technology finding better ways of peering into the unknown. Leonardo da Vinci's closely observed drawings gave doctors a better understanding of human anatomy. The discovery of X-rays made it possible to see the structure of the DNA molecule. More recently, progress has come from advances in artificial intelligence and a growing appreciation of the value of human history and diversity, among other things.

If science doesn't fully describe the practice of medicine, neither does technology completely explain its progress. Medicine is ultimately a practice of compassion, of caring for people. Recently, experts have come to believe that medical research and practice must strive to reflect the full diversity of the human species. This is not a platitude meant to signal virtue; it is essential to the task at hand. A diversity of researchers helps ensure that the medical issues that most people confront in their daily lives get attention. And in this age of AI, where data is king, including the full panoply of human biological diversity in the collection of that data helps those people who medicine has historically neglected—and, ultimately, everyone.

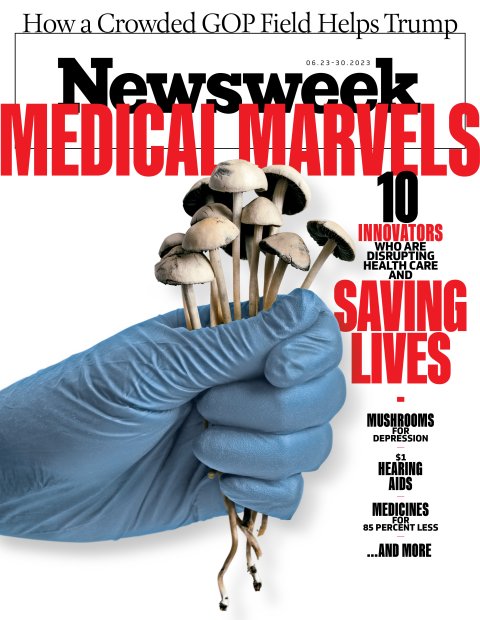

In this issue of Newsweek, we have chosen 10 visionaries who have carried this spirit of medical inquiry into the current age. This is the second group in a Newsweek series this year focusing on Great Disruptors—what we call innovative agents of change who are using technology in new and creative ways that could potentially improve our lives. This project has been months in the making. We have solicited nominations from more than 100 experts in a variety of fields. In addition, the Newsweek staff combed the work of universities, tech incubators, venture capital firms, futurists and other tech experts and organizations to identify worthy candidates.

All of these Great Disruptors are using technology in a way that is either already driving fundamental, transformative change in their field—typically, with measurable, real-world results—or has clear and demonstrable potential to do so. The projects and areas of expertise among the honorees who made the final cut are diverse. All are motivated by a genuine desire to do good—to help solve a problem of global proportions on their own smaller scale or to improve the lives of people and communities in need. They are passionate about their mission.

We find these extraordinary people inspiring. We hope you do, too.

If you are suffering—if you live with depression, anxiety, addiction or other mental health issues—there really is hope. Psychiatry has many effective tools, from medication and talk therapy to a range of behavioral treatments that have helped millions of people. Doctors wish they had more tools. The last major new class of drugs—antidepressants like Prozac, Lexapro and Zoloft—came in the 1980s.

But maybe there are other answers—much older ones, discovered by Indigenous people of what is now the Southwest, Mexico and parts of South America. Five thousand years ago, according to archeological evidence, some of them began to use psychedelics—compounds like mescaline, found in many types of cactus, and psilocybin, from certain mushrooms. Dr. Jeeshan Chowdhury is working to give these old remedies new attention.

Chowdhury is founder and CEO of Journey Colab, a San Francisco-based startup that hopes to market a synthetic form of mescaline. He says that if used in combination with mainstream psychotherapy, it could be a useful tool against addiction and, perhaps, other disorders. If its manufacture and use are approved, the fact that it's made in a lab means that plants in the wild need not be disturbed. And, importantly, Journey Colab has set up a trust to share ownership with the Indigenous people whose ancestors discovered the original compounds so long ago.

"These cultures are the only ones in the world that have successfully mastered at scale these very powerful technologies," Chowdhury says.

Much of mainstream medicine is skeptical of "magic mushrooms" and the like; the counterculture movement of the 1960s ("Turn on, tune in, drop out") backfired in many ways, leading to the war on drugs in the 1970s and after. Even the strongest advocates warn that if used carelessly, some psychedelics can do serious harm. People with family histories of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or cardiac problems should be especially careful. Chowdhury says mescaline needs to be used with safeguards, much as surgery is.

But there has also been promising research. For instance, researchers from Imperial College London used magnetic imaging to show that key networks in the brain "became more functionally interconnected and flexible after psilocybin treatment," they wrote in the journal Nature Medicine in 2022. A common antidepressant did not have the same effect. If psychedelics help the formation of new connections among brain cells, scientists say it may explain why some patients say they find new clarity, and better ways to handle their problems, in talk therapy afterward. It's not a drug trip that helps a person; it's an enhanced ability to find solutions in psychotherapy in the days that follow.

Chowdhury refers to Journey Colab as "Journey" when he talks. He says he's been on a journey of his own and an unlikely person to go exploring drugs that are illegal in the United States and many other countries. "I'm from a very traditional Muslim family," he says, "where even today, we don't have alcohol in our home."

Canadian-born, a doctor-turned-entrepreneur who started and sold a health care management firm, Chowdhury says life was going great—on the outside. "But on the inside," he says, "it always felt like I was drowning in my mental health." He suffered from an anxiety disorder, rooted in part in his family's struggles escaping war in Bangladesh, and prescription medications weren't enough. "It's not like they didn't work, but it was as if somebody threw me a life preserver and while I could keep my head above water, I never really got free."

Then he went to a therapist who gave him a small dose of a psychedelic—and in talk sessions afterward, the waters cleared. "What psychedelic medicine allowed for me was not only to know my own story, but to own my own story rather than being controlled by it."

A movement has grown, partly because of advocates like him, partly because of new science, partly because of increases in anxiety and depression that were worsened by the COVID-19 crisis. Oregon and Colorado have legalized psilocybin for adult use; esketamine, a newer compound, has FDA approval for controlled treatment of some people with depression.

Could psychedelic drugs, with careful controls, became a new tool to protect mental health? It's a complicated question, both medically and politically. But Chowdhury, for one, says he's hopeful.

"We're not asking anyone to trust us," he says. "We're saying to look at the data and see what we can do for patients and families who have had no other choices." —Ned Potter

One patient changed the course of thoracic oncologist Narjust Florez's career: a 43-year-old nonsmoker, an active runner, wife and mother who she'd just diagnosed with lung cancer. The patient's response? "Please don't tell my family."

More women die of lung cancer than any other cancer, including, since 2018, a growing number of young women. Many delay seeking treatment because of the stigma associated with lung cancer, including the idea that people brought the illness upon themselves—the same reason Florez's patient felt she couldn't tell her loved ones about her diagnosis.

Now, Florez is on a mission to change the way the world sees lung cancer and to improve screening processes so patients don't wait for treatment. She started the Florez Lab in 2019 to do that, but also to combat disparities in medical diagnosis and treatment affecting women, people of color, LGBTQ+ patients and non- English speakers. As a Latina woman, Florez is no stranger to discrimination in medicine herself. A 2021 study presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology showed that 53 percent of leadership positions in oncology training programs were held by white males, while only 2.9 percent were held by minority women.

To address the imbalance, Florez began a social media community called #LatinasinMedicine that connects seasoned physicians with mentees. The initiative eventually evolved into her Florez Lab, a research group of diverse medical practitioners focusing on lung cancer research and social justice, while also providing a support system for underrepresented physicians and aspiring doctors. The Lab has published more than 40 studies and operates cancer diagnostic clinics in underserved areas in Boston. One of their projects is collecting patient-reported data that shows the psychosocial and financial needs of patients of different ages, ethnicities and genders. The data helps care providers tailor specific treatment plans and is used as a basis for grant applications and future research. Florez is also the principal investigator for the FINCH study, a first-of-its-kind research project that measures short- and long-term effects of lung cancer and melanoma treatments on fertility and sexual health—a topic long taboo in oncology clinics.

Next up for Florez? She's implementing all that research to develop the first clinical program dedicated to young patients with lung cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, where she is the associate director of the Cancer Care Equity Program. The issue is closer to Florez's heart than ever now; last year, the woman she regards as a second mother—her mentor throughout medical school—was recently diagnosed with lung cancer. Says Florez, "[The diagnosis] solidified that my work and heart are in the right place." —Meghan Gunn

When Ryder founded Maven, now the world's largest virtual clinic for women's and family health, more than half of U.S. counties didn't have a single OB-GYN; few providers offered appointment hours before 9 a.m. or after 5 p.m.; and a lack of focus on female health issues was reflected in stats like the U.S. having the highest maternal mortality rate in the industrialized world. Ryder launched Maven in 2014 to try to fix all that—or at least sharply improve outcomes—by providing continuous, holistic care for patients through fertility, maternity, parenting, pediatrics and menopause. At the forefront of telehealth—the company served as a model for many of the virtual clinics started during the pandemic—Maven allows members to get customized care from anywhere, anytime.

It's a concept that quickly caught on, first with investors, then with patients and employers. Early backers included celebrities like Oprah Winfrey and Reese Witherspoon, as well as an assortment of venture capital funds, leading Maven to become the first "unicorn"—a startup valued at $1 billion or more—in the women's health space (its most recent valuation, as of November: $1.35 billion). The company now serves 15 million members across more than 175 countries and works with more than 500 employers to create lower-cost, higher-quality maternity health plans for employees, plus free access to telemedicine.

Among its innovative features: "Maven Wallet," which helps users calculate the cost of fertility, adoption, surrogacy and other reproductive health treatments, while expediting reimbursement from employers for out-of-pocket expenses. "Pregnancy Options" counseling helps guide members in the post-Roe era. The company is now also expanding to provide care for women and families enrolled in Medicaid and growing globally, facilitated by its recent acquisition of Naytal, a U.K. digital health platform with a provider network encompassing more than 25 specialties that will help Maven expand throughout Europe.

The real payoff, though, has been in the outcomes for members. One-quarter of Maven users seeking fertility help become pregnant without assisted reproductive technology; overall, the platform has driven a 28 percent reduction in neonatal intensive care unit admissions compared to the general population; and over 90 percent of members return to work after maternity leave, versus the national average of 57 percent. Says Ryder: "Whether it's the postpartum mom who was able to speak to a Maven lactation counselor in the middle of the night, or a same-sex couple who used Maven Wallet to navigate the financial complexities of their surrogacy journey, these stories are what keeps me and our team going every day." —M.G.

More than one-third of Americans, including nearly half of those with annual incomes below $50,000, have skipped taking prescribed drugs because of high prices—something former radiologist Alex Oshmyansky witnessed firsthand among his patients, sometimes with devastating health consequences. But the "straw that broke the camel's back was Martin Shkreli," he says. When Shkreli, a former pharmaceutical executive, raised the price of Daraprim, a lifesaving drug used to treat parasitic infections, by 5,400 percent from $13.50 a pill to $750 in 2015, Oshmyansky decided he would take on price gouging by the pharmaceutical industry himself by selling off-patent drugs at manufacturing costs.

To realize his goal, he reached out to Dallas Mavericks owner and Shark Tank star Mark Cuban for help, and together the pair last year launched Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, which sells common medications at dramatically lower-than-average prices by going directly to manufacturers to get their product, eliminating middlemen like wholesalers and pharmacy benefit managers that drive up costs to patients. The response was immediate: Some 1.3 million people signed up for accounts on its website in just its first 10 months, while sales hit at least $25 million in the first nine months, Forbes estimates. Cuban, though, says their real yardstick for success is "being able to reduce and someday eliminate patients having to choose between paying their bills and buying medications. Our hope is that we can bring transparency to an industry that has none."

In fact, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company puts its pricing formula right on its website for the 1,200 or so medications they currently sell: Using the manufacturer's price as a base, they add a 15 percent markup to cover their operating costs, a $3 pharmacist fee and $5 for shipping and handling. The result? Cholesterol-lowering med Rosuvastatin, the generic form of Crestor, costs $5.10 on their site, but retails for over $110 at other pharmacies. The generic version of diabetes medication Fortamet goes for $46.20 vs. $564 typically charged by other providers.

Since the launch, the company has been expanding its offerings rapidly, adding a wide variety of specialty drugs like Droxidopa (used to treat dizziness caused by diseases like Parkinson's) and Imatinib (for a form of leukemia), where savings can be more than a thousand dollars per month, and branded products from pharmaceutical makers J&J/Janssen, Pfizer, Coherus, IBSA and Roche. They've begun working with health insurers to allow customers to tap into their coverage for purchases and with pharmacies to add local pickup options. They're also opening a manufacturing facility in Dallas to produce medications that are in short supply directly for their customers.

Their latest disruption: Starting in July, the company will sell its first so-called biosimilar drug, Yusimry, an alternative to the immunology drug Humira, one of the bestselling medications of all time, at a cost of $569.27 plus dispensing and shipping fees, vs. $6,922 for a similar dosage of Humira. Announcing the news, Cuban tweeted: "The game has just changed." —Kerri Anne Renzulli

Contraceptives haven't advanced all that much since the 1950s, when women began taking "the pill"—usually a combination of estrogen and progestin—to stop ovulation. But Ukrainian-born physiologist Polina Lishko wasn't entirely satisfied with hormone treatments that put the onus for contraception entirely on women. She thinks science can do better.

Lishko has identified several compounds that inhibit the ability of sperm to move, which make the drugs good candidates for contraceptives. For this work, Lishko won a MacArthur "genius" award in 2020. One such drug, niclosamide, is known to be safe because it has already been approved by the FDA for treating tapeworm. Lishko thinks it could potentially provide an alternative to hormone treatments, probably as a topical contraceptive in a biodegradable vaginal film or ring.

What's needed next is to test these drug candidates on human eggs cells (which come with ethical challenges) and, eventually, in clinical trials. She co-founded the startup company YourChoice Therapeutics in part to attract the funds needed to bring these drugs to the marketplace.

In the lab, Lishko has other irons in the fire. She is trying to determine if the drop in hormones that women experience during menopause contributes to an increased risk of Alzheimer's. She's also developing a topical treatment to prevent macular degeneration, an eye disease that is a leading cause of blindness among people over 60. She's since started a second company, Biotock Therapeutics, that focuses on fighting such age-related diseases.

After a years-long struggle for resources, her research is now attracting funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and elsewhere. "Once the light is shed, it benefits the entire field," she says. "We should expect many breakthroughs in the very near future." —M.G.

High-tech solutions to the world's biggest health challenges typically share one critical impediment to mass adoption: cost. Medical innovation is expensive, which means lower-income individuals and poorer countries often can't afford to access it. Enter Saad Bhamla and his team of researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology's Bhamla Lab, all champions of "frugal science"—where the focus is on using simple concepts to develop low-cost technology that improves global health.

Consider, for example, their novel method for effectively delivering COVID-19 and other vaccines without some of the current costly requirements, such as ultra-low temperature storage. Inspired by the simple functionality of an electronic barbecue lighter, Bhamla and team created a low-cost handheld electroporation system, dubbed the "ePatch," which uses short electric pulses to drive molecules inside a cell—a critical step for mRNA vaccines to be successful—rather than relying on a chemical formulation as current vaccine delivery methods do. "Since it is locally applied with microneedles applied to skin, uses inexpensive pulse generators based on barbecue lighters and is simple to manufacture (lighters are commonplace, from Malawi to Afghanistan), our technology has the potential to bring the power of mRNA vaccines to everyone," Bhamla says.

Though the ePatch has successfully delivered COVID-19 vaccines in animals, Bhamla and his co-developers acknowledge it will need further refining and testing before it can begin human trials, expecting it will be at least five more years before their invention is ready for widespread use. To help that process, Bhamla co-founded Piezo Therapeutics, launched in January with $2 million in seed funding, to develop a simple, affordable and scalable platform to deliver nucleic acid medicines, including RNA/DNA vaccines. Also in the works separately at Bhamla Lab: a $1 hearing aid for age-related hearing loss. After a successful small pilot program last year, the lab is working to produce a commercial version in Malawi and India, having been awarded a Microsoft AI for Accessibility grant.

Not simply content with the here and now, Bhamla also has a keen eye on the future of frugal science. With a five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health, this year the Bhamla Lab launched the Frugal Science Academy, working with high school students across Georgia. Says Bhamla, "We're trying to create the next generation of scientists, and we're going to cultivate their ideas into products, and students into inventors and authors." —K.R.

Growing up in a conservative, religious Korean family who moved from Seoul to Los Angeles, Anna Lee never talked about sex. "I was afraid and ashamed of my body well into my mid-twenties, always wondering: Am I normal?" she says.

When she started to ask questions, she found copious information on male sexual function and how it relates to conditions like cardiovascular disease and overall well-being. There was little research available on female sexual health—even though, she says, "Orgasms are a canary in a coal mine for health conditions."

Lee's curiosity led her to an entirely new career path. In 2015, she quit her job as a mechanical engineer at Amazon to develop technology that provides feedback on female sexuality. Her startup, Lioness, developed a smart vibrator that uses precision sensors and artificial intelligence to provide biofeedback data. When paired with a mobile app, users can track how nutrition, sleep, caffeine, medications, stress and other factors affect their orgasms. (One Lioness user, after what she thought was a minor sports injury, saw that her orgasm data flatlined—a sign that she'd actually sustained a severe concussion.)

Lioness is also trying to expand the scientific understanding of female sexual function and health. By gathering data from its customers, Lioness claims to have amassed the world's largest database of physiological female sexual function (it has recorded data on more than 150,000 masturbation sessions). In 2022, the company collaborated with Jim Pfaus, director of the Sexual Neuroscience lab at Charles University in Prague, for a study on orgasms. The researchers identified three predominant patterns of female orgasms (ocean, avalanche and volcano). Lioness recently created a sex research platform that connects researchers with people interested in participating in new studies.

"There are a billion and three ways people experience sexual pleasure through all stages of life but not enough of them are represented in sex tech quite yet," says Lee. "My goal at Lioness is to continue to bring representation for all walks of life in both sex research and products." —M.G.

In his later years, the physicist Stephen Hawking, partially paralyzed by ALS, was unable to speak and could communicate only by typing out sentences letter by letter, using facial movements, into a voice synthesizer. A response to one reporter's question—"I hope my experience helps other people"—took the scientist five minutes to formulate.

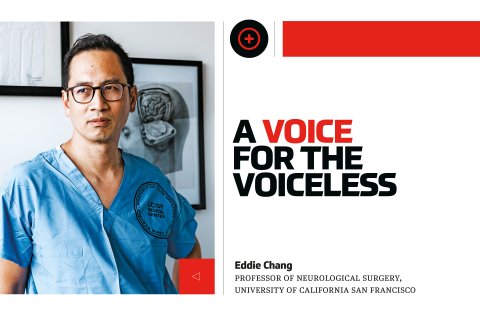

Eddie Chang envisions a world in which everyone can converse easily and freely with the people around them, even if their paralysis is so severe that they cannot produce vocal sounds. To this end, Chang developed a "speech neuroprosthesis" that turns electrical signals of the brain into words on a computer screen and, ultimately, into oral language.

The key to Chang's invention was his discovery of electrical patterns that the human brain uses to produce consonants and vowels in speech. Next, he built a device that converts these brain patterns directly into spoken language. In 2021, Chang and his team tested such a device on a man in his late thirties who had suffered a major stroke and had to use a pointer attached to a baseball cap to indicate letters on a screen. Chang surgically implanted a device into the man's brain that accurately picked up brain signals associated with the words "water," "family," and "good." Chang's colleague added an auto-correct function, like those used for speech recognition software. This resulting device could decode words from those brain signals at a rate of 18 words per minute with a median accuracy of 75 percent.

"We are making significant progress on making it faster, more accurate and with a large vocabulary," says Chang. The work was a first step to developing a device that, Chang hopes, will eventually provide a true alternative to natural speech. —M.G.

Mary Lou Jepsen seems to have lived many lives. In her twenties, she created the first hologram video system, played in a band, hung out with Lou Reed and Andy Warhol and began a doctoral degree at Brown University. Then she was overtaken by a mysterious illness that not only left her physically bedridden and wheelchair-bound, but also rendered her unable to do the high-level math she needed to do to complete her degree. Even simple arithmetic eluded her.

"I was utterly defeated," she says. "I went home to die."

Her professors chipped in to cover the cost of an MRI. Her doctors found a brain tumor that was inhibiting her pituitary gland. After they removed the tumor and part of the gland, her mental powers returned. She experimented with different hormones and dosages until she hit upon a combination that enabled her to return to her studies and finish her Ph.D.

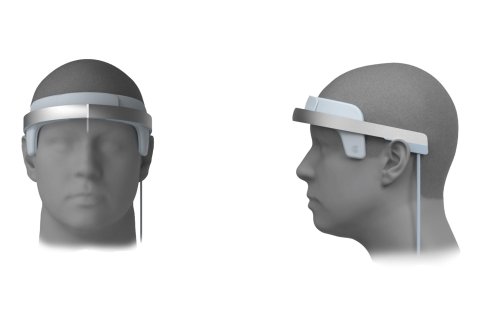

Jepsen went on to have an outstanding career in consumer electronics. As executive director of engineering at Facebook's Oculus division, she drove the future of augmented and virtual reality, overseeing the introduction of the first Oculus Rift headset in 2016. But she wanted to apply her knowledge of consumer electronics and physics to a field closer to her heart: medicine—specifically, neural diseases and cancers.

Jepsen left Facebook and founded Openwater with the goal of developing wearable devices that provide an alternative to radiation treatment and surgery in treating brain tumors. The devices, currently prototypes, send beams of ultrasound into the brain at low intensities—lower than those of ordinary diagnostic equipment used to image fetuses. But the frequencies of the ultrasound are tuned to target cancer cells, destroying them in the same way the soprano voice of an opera singer can break a wine glass. Since the healthy brain cells that surround the cancer have mechanical properties different from aggressive cancer cells, the ultrasound has no effect on them.

Openwater is wrapping up a proof-of-concept study on mice. So far, the devices have successfully shrunk tumors in glioblastoma cases almost completely. Jepsen says the devices could hit the market as soon as next year. She expects them to have wide-ranging applications across hundreds of different conditions, from depression to neurodegenerative diseases to strokes. She plans to sell them at low costs to companies, universities and R&D labs. For Jepsen, the transition to medicine was only natural: "Without our health," she says, "we have nothing." —M.G.